Japanese anime has evolved over roughly 100 years, winning huge acclaim both at home and abroad. The term anime has become globally recognized as referring specifically to Japanese-style animation, and today anime is an indispensable part of world pop culture. Beginning in the 1980s, Japanese animated shows and films started appearing more often on Western TV and in media, and the word “anime” itself became a generic term worldwide.

This article traces the journey of anime from its birth to the present day. We’ll cover the early days of TV anime, the nationally beloved hits of the Showa era, the global expansion since the 2000s, and the evolution of otaku (fan) culture in Japan. The writing is aimed at overseas fans and anyone interested in Japanese culture, with a factual and internationally relevant perspective. To make it easy to follow, we’ll clearly lay out each point, explain why it matters, give examples, and wrap up the conclusion.

Contents

Birth and Early Days of Japanese Anime

Japanese animation production began around 1917, inspired by Western short cartoons. That year saw Japan’s first animated film, and in the years that followed animators experimented with hand-drawn and cutout techniques. By 1929 sound cartoons (talkies) were common abroad and color film arrived in 1932, but Japanese animation couldn’t keep up and fell on hard times.

Even so, animator Noburō Ōfuji made waves with a paper-cutout animation called Chiyogami Anime. This work earned high praise internationally and introduced the name of Japanese animation to the world. Near the end of World War II, the Japanese Navy produced a propaganda anime film called Momotaro’s Divine Soldiers at Sea (1945). At 74 minutes long (black and white), it was Japan’s first animated feature film. It’s often seen as a culmination of the prewar animation techniques and was a significant work for its time.

After the war, the Allied GHQ (General Headquarters) even tried to form official animation studios in Japan, but the country was still in chaos and those efforts never really took root. Even so, these early attempts helped train the first generation of animators and technical staff. Gradually, on a small scale at first, Japan began to build its own unique animation production base.

Showa Era: Emergence of Nationally Popular Anime

Innovation in TV Anime

In the 1950s and 1960s, as television became widespread in Japan, the first homegrown TV anime series were born. Osamu Tezuka’s Mushi Production (founded in 1961) aired Tetsuwan Atom in 1963 – better known to the world as Astro Boy. This 30-minute weekly series established the basic format for future TV anime and is often cited as the pioneer of Japanese television animation.

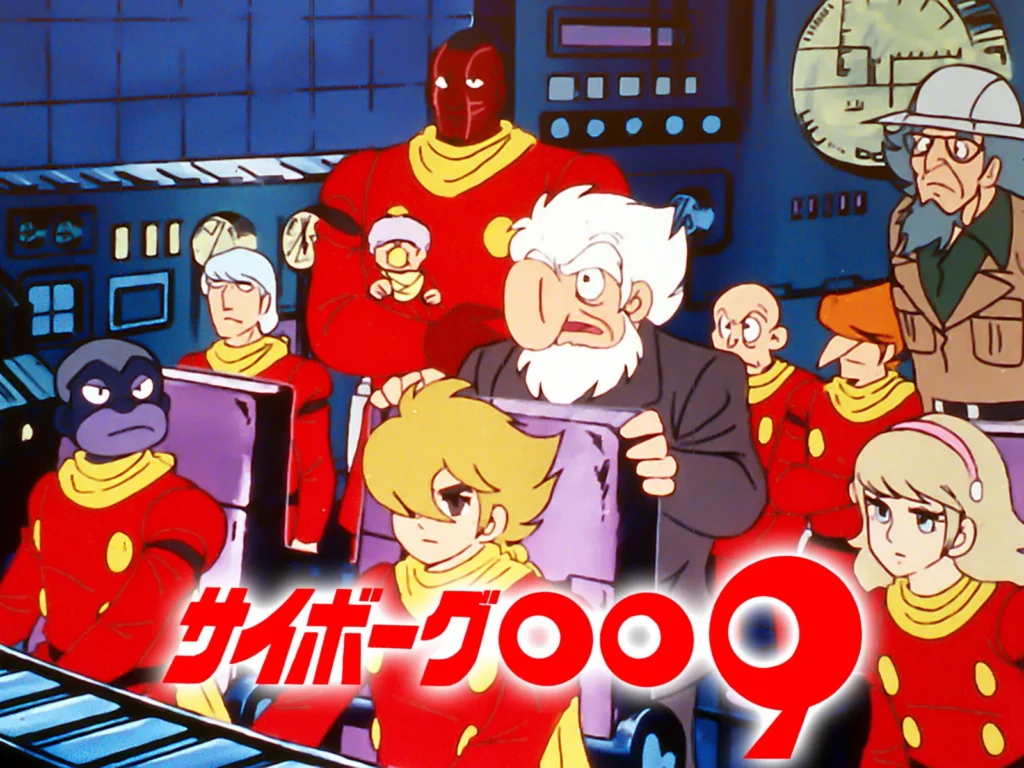

Astro Boy was even shown in the United States on NBC under its English title, becoming an early international hit. Its initial episodes, some of which were broadcast in color, drew a massive 40.3% audience rating, and over its four-year run it generated roughly 500 million yen in licensing revenue. This huge success proved that TV anime could be commercially viable. In the same year, Toei Doga (now Toei Animation) joined TV with Ōkami Shōnen Ken (Wolf Boy Ken, 1963), and by the late 1960s was producing series like Cyborg 009 (1968).

Astro Boy’s success also pioneered Japan’s first media-mix model: a manga published in magazines that was adapted into a TV series and then compiled into books. This multi-platform approach helped drive the growth of Japan’s anime industry.

Late Showa Era Hit Series

By the late Showa period (roughly the 1960s–80s), a wide range of anime genres had captured the nation’s imagination. Notable works from this era include:

- Astro Boy (Tetsuwan Atom) (1963–1980): As mentioned above, this was Japan’s first full-scale TV anime (based on Tezuka’s manga). It won national popularity with its weekly 30-minute episodes, and even aired on NBC in the U.S., proving a brilliant international business model.

- Sazae-san (1969–present): A home comedy based on Hasegawa Machiko’s manga. It depicts the everyday life of a family and has been on the air continuously for over half a century. It’s one of Japan’s longest-running shows and is widely loved as a cultural icon.

- Doraemon (1979–present): A sci-fi comedy by Fujiko F. Fujio about a cat-like robot from the 22nd century. Since its TV anime debut in 1979, Doraemon has been adored by children and remains a national favorite.

- Mobile Suit Gundam (1979–1980): A mecha (robot) anime by Sunrise. It used a media-mix strategy tied to its toy line to overcome initially low TV ratings, eventually launching a new era of giant-robot series.

- Dragon Ball Z (1989–1996): An action anime based on Akira Toriyama’s manga. It achieved fanatical popularity in Japan and around the world, becoming one of the drivers of the global anime boom.

- Pokémon (Pocket Monsters) (1996–present): Using a media-mix strategy linked to its video games, it became a worldwide hit. Beyond the TV show, the Pokémon franchise expanded into mobile games, card games, toys, and a vast range of merchandise, capturing an international fan base.

In the 1980s these trends continued alongside new developments. The OVA (Original Video Animation) market took off, allowing anime creators to produce works for niche and adult audiences that wouldn’t fit on regular TV broadcasts. In the film world, Studio Ghibli releases and other high-profile movies appeared with cinema-quality animation and mature stories. For example, AKIRA (1988, directed by Katsuhiro Otomo) showcased art and themes on par with live-action films and developed a cult following overseas.

Together, these developments meant that during the Showa era anime expanded from being just for kids to including works enjoyed by adults as well. By the end of that period, anime had truly become a hallmark of Japanese pop culture.

Global Expansion Since the 2000s

From the 2000s onward, Japanese anime has benefited hugely from the Internet and digital technology, spreading around the world like never before. Video-sharing sites and social media allowed new anime series to be distributed in real time globally, and dedicated fan communities sprang up mainly among young people in the West and Asia. One industry survey by Dentsu reported that Japan’s domestic anime market reached a record 2.7422 trillion yen in 2021 – about double what it was ten years earlier. This rapid growth has been driven in part by the rise of streaming services and the increase in home viewing during the COVID-19 pandemic.

International recognition of anime also shot up. Japanese animated films have racked up major awards at film festivals. Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away (2001) won the Golden Bear (the top prize) at the 2002 Berlin International Film Festival, and in 2003 it went on to win the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature. This was the first time a Japanese animated feature had won an Oscar – a feat that, as of 2024, remains unique. Other films, like Howl’s Moving Castle (2004) and Your Name. (2016), also saw both commercial and critical success, helping to cement the international stature of Japanese animation. In the late 2010s, anime using advanced CG and digital techniques – even experimental interactive VR anime – started appearing as well.

On television, series like Naruto, One Piece, Death Note, and Attack on Titan became huge hits in the U.S., Europe, and across Asia. These shows were translated and dubbed into many languages for worldwide distribution. From the late 2000s, streaming platforms such as Crunchyroll, Netflix, and Amazon Prime Video jumped into the anime scene, making unprecedented volumes of Japanese anime available to global audiences.

With smartphones and social media, fan communities expanded rapidly across borders. International anime events – such as Anime Expo in the U.S. and Japan Expo in France – began to be held on a large scale around the world. In this way, venues for fan exchange multiplied globally, and “anime” truly became a worldwide cultural phenomenon.

Otaku Culture Goes Mainstrea

The social image of otaku (the term for hardcore fans of anime and related media) has also changed dramatically. Through the 1980s, just being called an “otaku” carried social stigma, as if it meant a person had a closed-off or antisocial hobby. However, from the 2000s onward, things began to shift. With the Internet making it easy to share information and with enthusiastic praise from abroad, ordinary Japanese people have grown to understand and accept otaku culture. Recent surveys find that about 45% of Japanese now say they have a more positive view of “otaku” than in the past, and this positive perception is especially strong among younger generations.

Places like Akihabara in Tokyo have become centers of otaku culture, filled with specialty shops for anime, games, and cosplay. These districts have turned into tourist destinations where visitors can experience the otaku world firsthand. Events like Comiket (a massive self-published comics fair) and various anime conventions continue to flourish, making otaku gatherings into occasions for international exchange as well. According to market research firm Yano (矢野経済研究所), it’s even predicted that by 2030, around 30–40% of Japan’s population could be identified as “otaku,” pointing to a major expansion of this market.

Academia and government have also taken note. Universities are increasingly offering courses on anime and manga, and anime culture is being covered in lectures for international students. Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs is actively collecting and preserving original manga artwork and anime storyboards, recognizing that these works are gaining value as cultural heritage. Altogether, otaku culture has shifted from a niche hobby to something much more mainstream, and its social status has clearly improved compared to the past.

Cultural Exchange Through Anime

Anime today also serves as a window into Japanese culture for people around the world. Many foreigners become fascinated by the Shinto shrines, scenic landscapes, and Japanese phrases that appear in anime stories. In some cases, this interest even motivates them to study the Japanese language or to pursue education in Japan. The Japanese government and other organizations have launched cultural exchange programs centered on anime, aiming to promote international understanding through this art form.

Furthermore, exhibitions of Japanese anime are now being held in museums and art galleries around the globe, enhancing anime’s reputation as a form of artistic expression within pop culture. Through these channels, anime continues to build bridges between Japan and other countries, underscoring its role not just as entertainment but as a form of cultural diplomacy.

Cultural Conclusion

As we’ve seen, Japanese anime began by adopting techniques from Western animated films, took off during the Showa era to win the hearts of the Japanese public, and has since become a global phenomenon. Today there are more co-productions between Japan and overseas creators than ever, showing that anime is becoming a truly shared international content. In emerging markets from Africa to South America, anime is growing in popularity, suggesting that the potential market for Japanese animation could expand even further. Local creators in many countries are now producing works in a Japanese anime style as well, highlighting the far-reaching influence of anime.

In short, anime has grown from its humble, century-old beginnings into a worldwide cultural force. Its journey continues, and its future impact on global entertainment and cultural exchange looks as vibrant as ever.